“With all our institutions, from the police force to academia, from medicine to politics, we give little attention to the people who leave—that process of elimination that goes on all the time and which excludes, very early, those likely to be original and reforming, leaving those attracted to a thing because that is what they are already like.” (Doris Lessing)

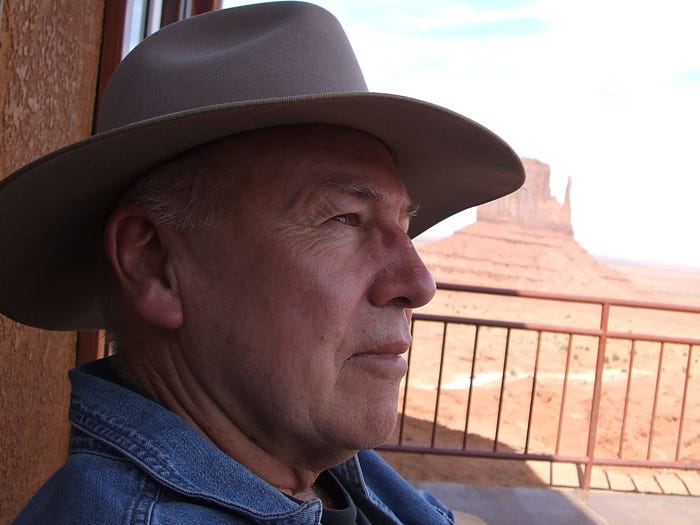

I was hanging out with my wife on the south coast of Crete, in a block shelter on the sea cliff between Pitsidia and Matala Bay. I’d just quit my job at the Arizona Republic’s Arizona Magazine. A guild was forming, and management was pissed off about it and froze all the wages. They brought in a thug from Oakland, who was advertised as a war hero but was never actually in the military, we later discovered. His partner in crime was a thin, slightly stooped, middle-aged man with bad complexion. He was “Personnel Director.” The big guy intimidated physically and his cohort intimidated with performance reviews.

When there was a readership survey, we came in above the front page, which, management said, had to be a mistake. We had a readership of 700k. When I got my next review, it rated me as average. I asked my editor why he did that, and he said he didn’t do it. It came from the front office, which meant the new Personnel Director. I gave two weeks' notice. During that two weeks, I got two raises, but as the review was not changed, I left.

One of the subjects I’d written about was the Meyers Briggs personality test, and of course, I took the test. It suggested that I’m the kind of person who likes to work by myself. I had been happy so long as I’d been left alone to do my job, but now that was over.

The guild coming in meant I’d have to take a photographer with me when I traveled, and I liked doing my own photography. And there was the new atmosphere of intimidation. It had been a great job while it lasted, but I was going to move on.

So there I was on the island of Crete, aware that I would never get a positive job referral from the Republic, having antagonized top management. I didn’t care. I wanted adventure, not security. I never worked for a corporation again. I never worked for anybody else again. As suggested by Myers and Briggs, I like to work on my own.

There have been a few times in my life when I said something that I didn’t consciously believe, but it turned out to be the truth when I said I wasn’t writing any more until I had something important to say. I had read about a faculty allowing direct communication, mind to mind, in accounts of Gurdjieff and others. I wanted to learn how to do that.

“To a philosopher all news, as it is called, is gossip, and those who edit and read it are old women over their tea.” (Thoreau)

I had gone to ASU to pick up a journalism degree. At 21, I had been a Navy journalist and was offered an assistant editor’s job on a small daily, so I didn’t need training. I just wanted the degree, so I turned down the job to go to school on the GI Bill. I was supporting myself by editing two community weekly newspapers, putting what I learned in editing class right to work. I took them and showed them to the editing prof. He and the head of the department said I could choose either do the editing lab that was required on the school paper or quit college. I don’t have to explain how idiotic that was. I worked in a hot dog stand near the campus until I got a good job that I could do part-time.

I found a good job posted on a bulletin board at the university.

Thus, in my junior year at ASU, I became Public Relations Director for Realty Executives, writing press releases and recruiting new salespeople with slide presentations, brochures, etc. I did them all myself, spending almost no money, which was great for Dale Rector, who started the firm.

He liked me so much that he gave me the corporate advertising account when I graduated and joined an advertising agency. I was getting results from direct mail marketing of about 5% when the average was 1%. I was too young and inexperienced to know how much money that was worth.

I was writing freelance for the Arizona Magazine on the side, and they offered me the full-time job. The editor, who became a good friend and ally, told me in the interview that I had a reputation as a loose cannon but that he liked having one of his writers be a loose cannon because they are almost always the best writers.

While getting the journalism degree, I had to take electives, and one of them I chose was American Cultural History. It sounded like an easy course. The prof was an intellectual version of Elvis. He wore a denim jacket and wore his hair in what I remember as a ducktail. He didn’t care if you smoked in class, and he got so lost in his lecture he would forget where he was, suddenly looking up, surprised to see us taking notes. “You don’t need to take notes,” he said. “You’ll understand the ideas or not, but notes won’t help much.”

I had a new role model.

He introduced me to Faulkner, William James, Henry James, Ralph Ellison, Mary Baker Eddy’s Christian Science movement, the Mind Cure Movement, Archibald McLeash at the end of the world, and more. The next semester I took American Intellectual History from him, and the next semester, The Mind of the South. He was by far the most influential professor I had. By contrast, the Journalism Department at ASU in the seventies was a clown show.

When I was free to adventure, I started with a coin toss.

After some downtime in Europe, my wife and I moved from Phoenix to San Francisco, and I worked with her for a couple of years to get her tax accounting business going . I began to learn books on hypnosis and healing by rewriting them in my own words, so that I was incorporating them into my understanding. I read books by and about Janet, Freud, Charcot; I read obscure books on healing, one by a nun, investigated Phineas Quimby, Felex Kirstin, Rolf, Feldenkrais, Traeger, everything I could lay hands on. I was reading Jung and Jungians, of course, and would later do a four-year analysis with Dr. Joseph Henderson, one of Jung’s major proteges, as well as investigate pattern-level psychology with the brilliant Dr. Brugh Joy. I studied Ericksonian hypnosis with a psychology prof from Monterey. I started getting a private clientele, seeing people by referral only, so that I could control my schedule and work when I pleased with whom I pleased. It allowed me to investigate the direct communication by choosing two or three clients who were particularly sensitive senders and receivers and unconventional enough to understand the nature of the energy we were using. This also allowed a lifestyle in which work was not separated off from just practicing an art.

When I had not written regularly for a few years, and started to write again, I realized it’s like playing a sport. You still know how to play, but you’re not that good at it anymore. Now I write almost every day to keep on my game. Usually, I think of the thematic core of a story when I’m walking, or it comes from a news report or a book I’m reading. I sit down in the early afternoon and see where it takes me. I write very quickly and don’t rewrite. I edit though. And when I am writing, I make myself laugh. I love to laugh. I think it helps to keep me young, at 74.

My current wife told me that she knew when I was twenty and she was 17, that we were a good match, but it took me thirty-plus years to admit to myself that she might be right. There are surprisingly few people who really match up with an eccentric loose cannon.

She said the only woman who can handle me is a professional manager, which she is. She’s a genius, and she always loved me without any conditions, teaching me, by example, to love other people unconditionally. Quite a trip from where I started. I knew, intellectually, the concept of it, but direct experience of it is invaluable.

You’ve led an interesting professional life, Dan, and that clearly informs your fiction. Like you I worked out after a few years that I wasn’t employee material, had no patience for corporate political shenanigans. With that epiphany, and a fair measure of good luck, everything fell into place.